Blockchain Privacy: Monero vs Zcash vs Canton Network

One of the defining narratives of 2026 is ‘Privacy’. As institutional players take on a dominant role in crypto, privacy has become a critical technical feature for bridging blockchain with real-world business.

Key Takeaways

- Blockchain’s core advantage of transparency can expose corporate trade secrets and investment strategies, creating material risk for enterprises.

- Fully anonymous privacy models like Monero do not support KYC or AML, making them unsuitable for regulated institutions.

- Financial institutions need selective privacy that protects transaction data while remaining compatible with regulatory oversight.

- Financial institutions must determine how to connect with open Web3 markets for expansion.

1. Why Is Blockchain Privacy Necessary?

One of blockchain’s core features is transparency. Anyone can inspect on-chain transactions in real time, including who sent funds, to whom, in what amount, and at what time.

Viewed from an institutional perspective, however, this transparency raises clear issues. Consider a scenario where the market can observe how much Nvidia transfers to Samsung Electronics, or precisely when a hedge fund deploys capital. Such visibility would fundamentally alter competitive dynamics.

The level of information disclosure that individuals can tolerate differs from what corporations and financial institutions can accept. Transaction histories of enterprises and the timing of institutional investments constitute highly sensitive information.

As a result, expecting institutions to operate on blockchains where all activity is fully exposed is not a realistic proposition. For these actors, a system without privacy is less a practical infrastructure and more an abstract ideal with limited real-world applicability.

2. Forms of Blockchain Privacy

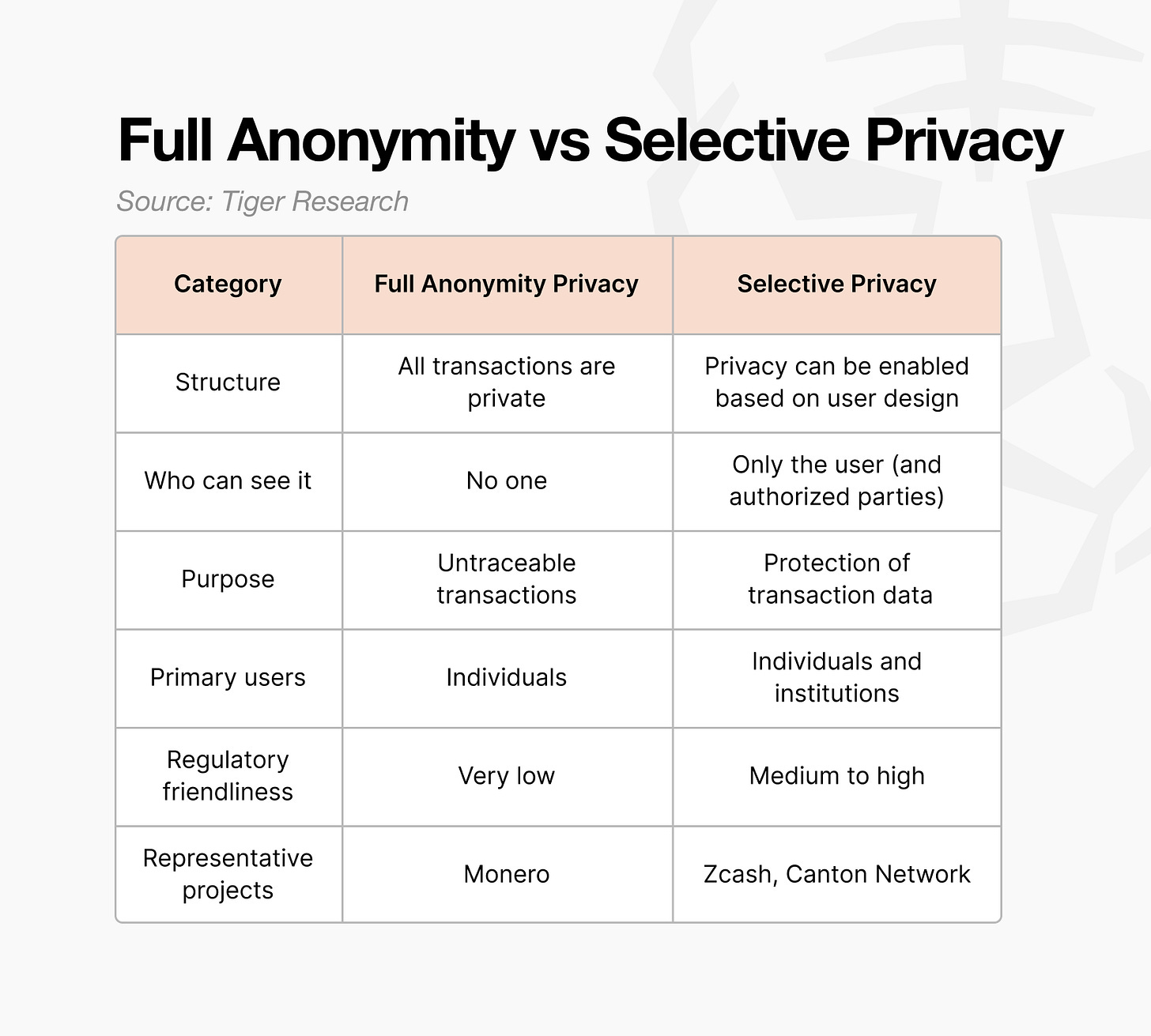

Blockchain privacy generally falls into two categories:

- full anonymity privacy

- selective privacy.

The key distinction lies in whether information can be disclosed when verification is required by another party.

2.1. Full Anonymity Privacy

Full anonymity privacy, put simply, conceals everything.

The sender, the recipient, and the transaction amount are all hidden. This model stands in direct opposition to conventional blockchains, which prioritize transparency by default.

The primary objective of full anonymity systems is protection from third-party surveillance. Rather than enabling selective disclosure, they are designed to prevent external observers from extracting meaningful information altogether.

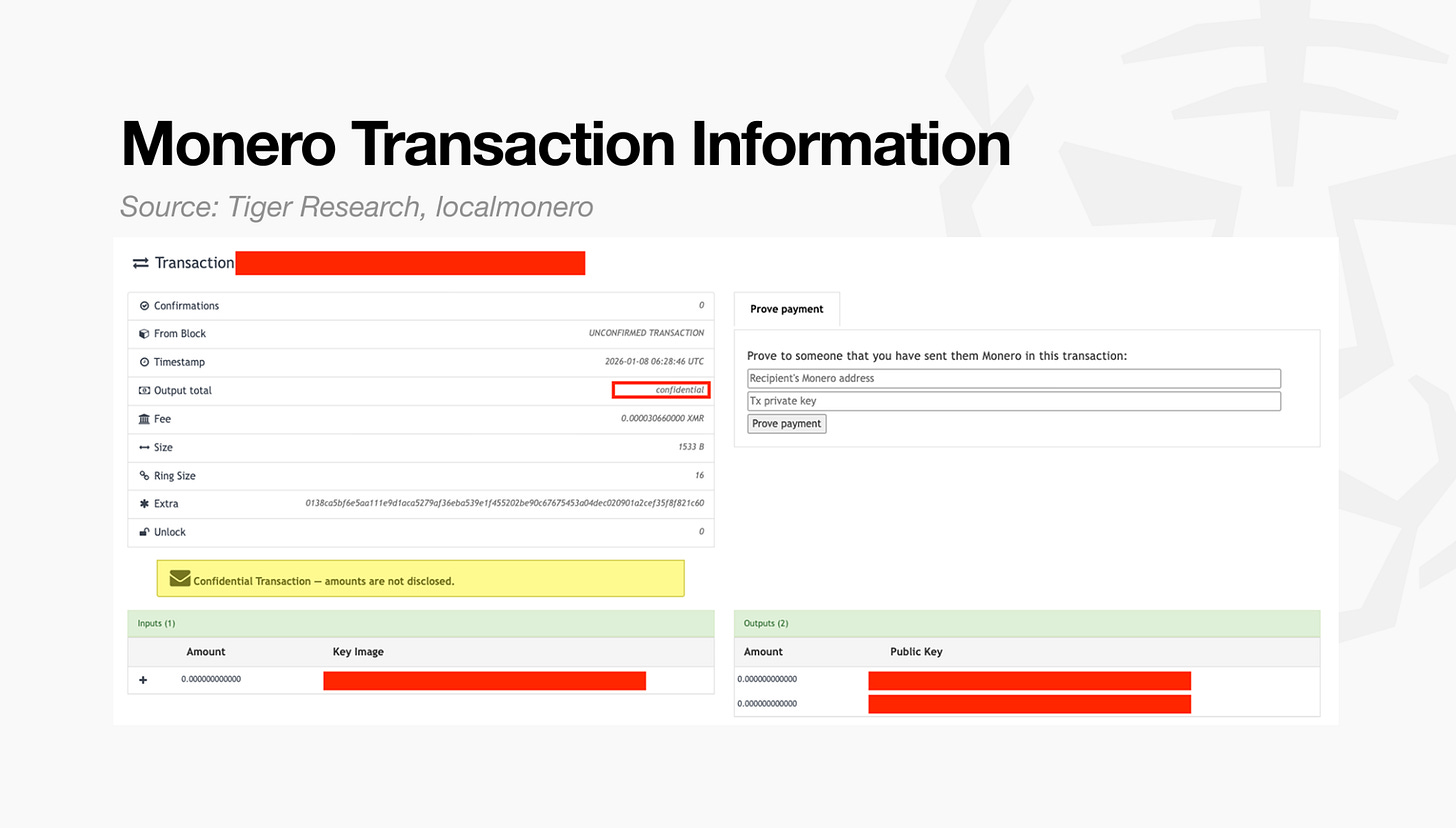

The image above shows transaction records from Monero, a representative example of full anonymity privacy. Unlike transparent blockchains, details such as transfer amounts and counterparties are not visible.

Two features illustrate why this model is considered fully anonymous:

- Output Total: Instead of a concrete number, the ledger displays the value as “confidential.” The transaction is recorded, but its contents cannot be interpreted.

- Ring Size: Although a single sender initiates the transaction, the ledger mixes it with multiple decoys, making it appear as if several parties sent funds simultaneously.

These mechanisms ensure that transaction data remains opaque to all external observers, without exception.

2.2. Selective Privacy

Selective privacy operates on a different assumption. Transactions are public by default, but users can choose to make specific transactions private by using designated privacy-enabled addresses.

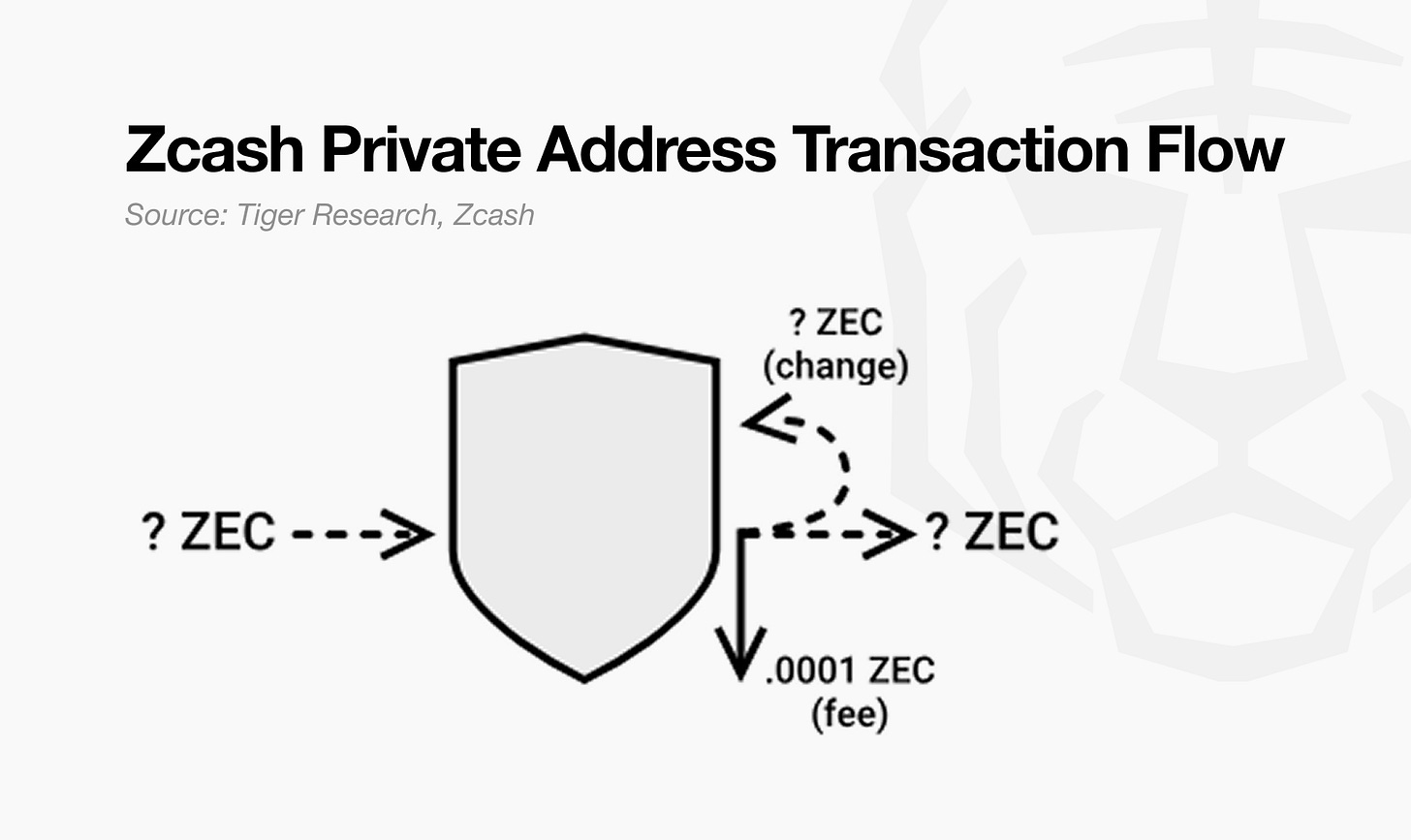

Zcash provides a clear example. When initiating a transaction, users can choose between two address types:

- Transparent Address: All transaction details are publicly visible, similar to Bitcoin.

- Shielded Address: Transaction details are encrypted and concealed.

The image above illustrates which elements Zcash can encrypt when shielded addresses are used. Transactions sent to shielded addresses are recorded on the blockchain, but their contents are stored in an encrypted state.

While the existence of a transaction remains visible, the following information is concealed:

- Address type: Shielded (Z) addresses are used instead of transparent (T) addresses.

- Transaction record: The ledger confirms that a transaction occurred.

- Amount, sender, recipient: All are encrypted and cannot be observed externally.

- Viewing access: Only parties granted a viewing key can inspect the transaction details.

This is the core of selective privacy. Transactions remain on-chain, but users control who can view their contents. When necessary, a user can share a viewing key to prove transaction details to another party, while all other third parties remain unable to access the information.

3. Why Financial Institutions Prefer Selective Privacy

Most financial institutions are subject to Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) obligations for every transaction. They must retain transaction data internally and respond immediately to requests from regulators or supervisory authorities.

In environments built on full anonymity privacy, however, all transaction data is irreversibly concealed. Because the information cannot be accessed or disclosed under any condition, institutions are structurally unable to fulfill their compliance obligations.

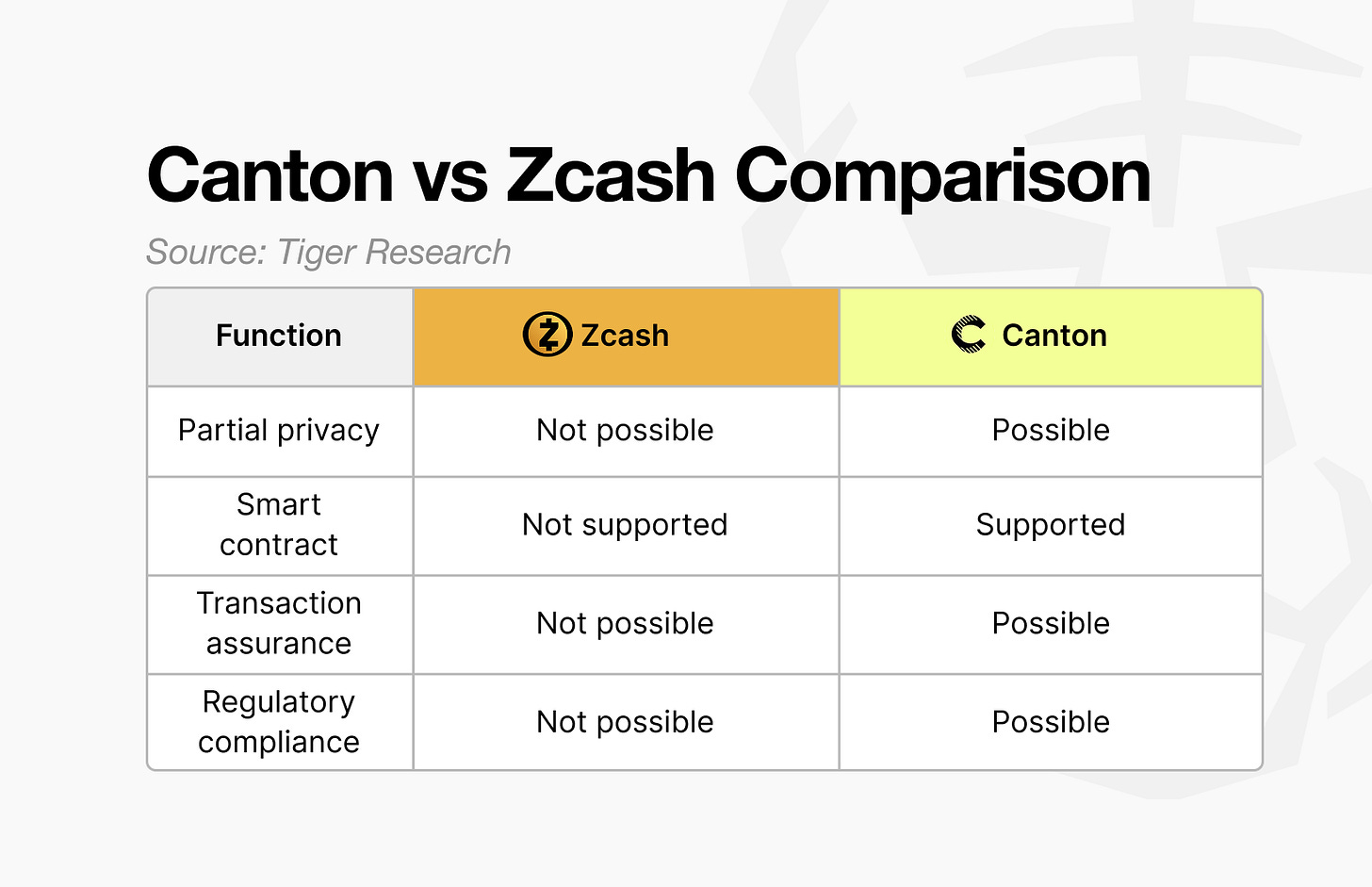

A representative example is Canton Network, which has been adopted by the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) and is already used by more than 400 companies and institutions.

By contrast, Zcash, despite also being a selective privacy project, has seen limited real-world institutional adoption.

What accounts for this difference?

Zcash offers selective privacy, but users do not choose which pieces of information to disclose. Instead, they must choose whether to disclose the entire transaction.

For example, in a transaction where “A sends B $100,” Zcash does not allow only the amount to be hidden. The transaction itself must either be fully hidden or fully disclosed.

In institutional transactions, different parties require different pieces of information. Not all participants need access to all data within a single transaction. However, Zcash’s structure forces a binary choice between full disclosure and full privacy, making it unsuitable for institutional transaction workflows.

Canton, by contrast, allows transaction information to be managed in separate components. For example, if a regulator requests only the transaction amount between A and B, Canton enables the institution to provide only that specific information. This functionality is implemented through Daml, the smart contract language used by the Canton Network.

Additional reasons why institutions have adopted Canton are covered in more detail in prior Canton research.

4. Privacy Blockchains in the Institutional Era

Privacy blockchains have evolved in response to changing demands.

Early projects such as Monero were designed to protect individual anonymity. As financial institutions and enterprises began entering blockchain environments, however, the meaning of privacy shifted.

Privacy is no longer defined as making transactions invisible to everyone. Instead, the core objective has become protecting transactions while still meeting regulatory requirements.

This shift explains why selective privacy models such as Canton Network have gained traction. What institutions required was not privacy technology alone, but infrastructure designed to match real-world financial transaction workflows.

In response to these demands, more institution-focused privacy projects continue to emerge. Going forward, the key differentiator will be how effectively privacy technology can be applied to actual transaction environments.

There may be alternative forms of privacy that arise in opposition to the current institution-driven trend. For the near term, however, privacy blockchains are likely to continue evolving around institutional transactions.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [Tiger Research Reports]. All copyrights belong to the original author [Tiger Research Reports]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?