Anthropic just released a report titled "AI Steals Jobs": the higher the education level, the more jobs are being taken away.

Anthropic published its “Economic Index Report” on its official website yesterday.

The report explores not only how people use AI, but also the extent to which AI is genuinely replacing human thought.

This time, Anthropic introduced a new framework called “Economic Primitives,” designed to quantify task complexity, required educational attainment, and the degree of AI autonomy.

The workplace future revealed by the data is far more nuanced than simple narratives of “unemployment” or “utopia.”

The More Complex the Task, the Faster AI Delivers

Traditionally, machines are thought to excel at repetitive, simple tasks, but struggle in domains requiring advanced expertise.

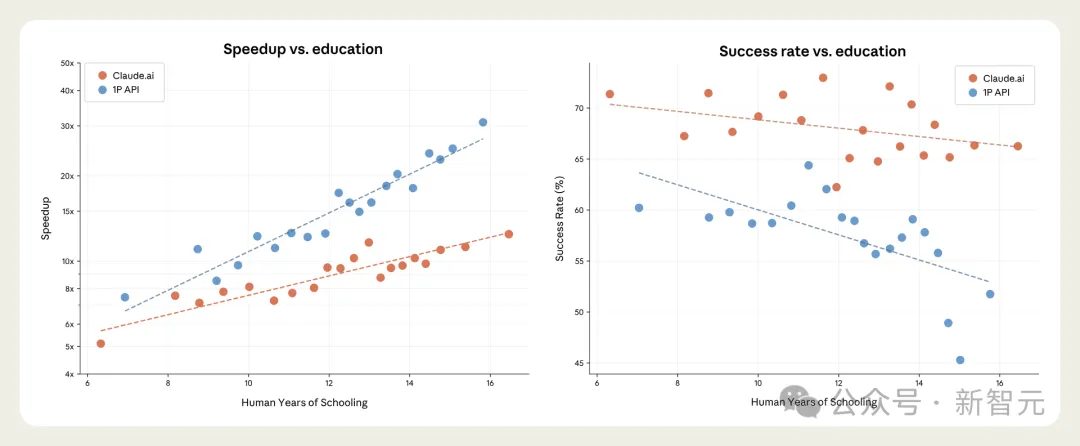

Anthropic’s data shows the opposite: the more complex the task, the more dramatic the acceleration powered by AI.

According to the report, for tasks requiring only a high school education, Claude can boost work speed ninefold.

When task complexity rises to the level of a college degree, this acceleration jumps to twelvefold.

This means the kinds of white-collar jobs that once demanded hours of deep thought are now where AI achieves peak efficiency.

Even factoring in the occasional error or hallucination, the conclusion holds: the surge in efficiency AI brings to complex tasks more than offsets the cost of correcting its mistakes.

This explains why programmers and financial analysts rely on Claude more than data entry clerks—AI delivers the greatest leverage in high-intellect fields.

19-Hour Human–AI Collaboration: The “New Moore’s Law”

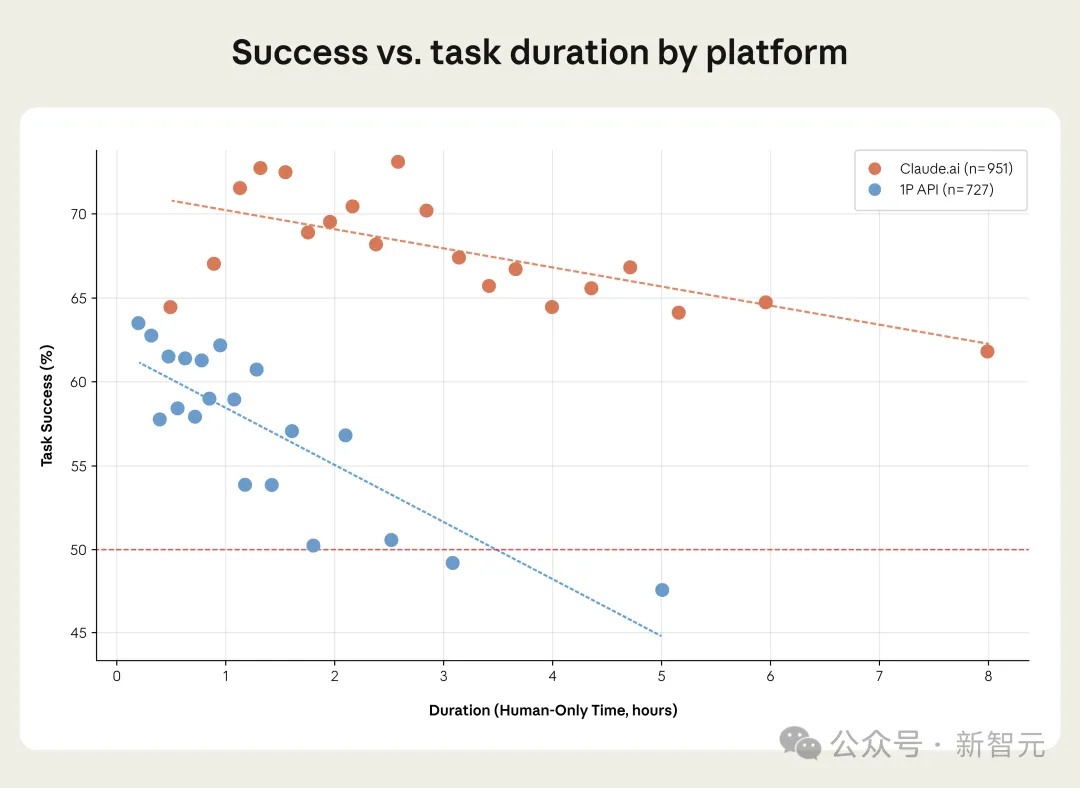

The report’s most striking finding is its test of AI “endurance”—task duration, measured at a 50% success rate.

Standard benchmarks like METR (Model Evaluation & Threat Research) show that leading models (such as Claude Sonnet 4.5) fall below a 50% success rate when handling tasks that take humans two hours.

Yet Anthropic’s real-world user data reveals a much longer time horizon.

In commercial API scenarios, Claude maintains a greater-than-half success rate on tasks requiring 3.5 hours of work.

On the Claude.ai chat platform, that number soars to 19 hours.

What accounts for this dramatic difference? The key is human involvement.

Benchmarks test AI in isolation, but real users break complex projects into small steps and continually guide AI through feedback loops.

This human–AI workflow extends the 50% success threshold from 2 hours to about 19 hours—a nearly tenfold increase.

This may be the future of work: not AI operating independently, but humans learning to harness it for long-haul projects.

Global Map: The Poor Learn, The Rich Produce

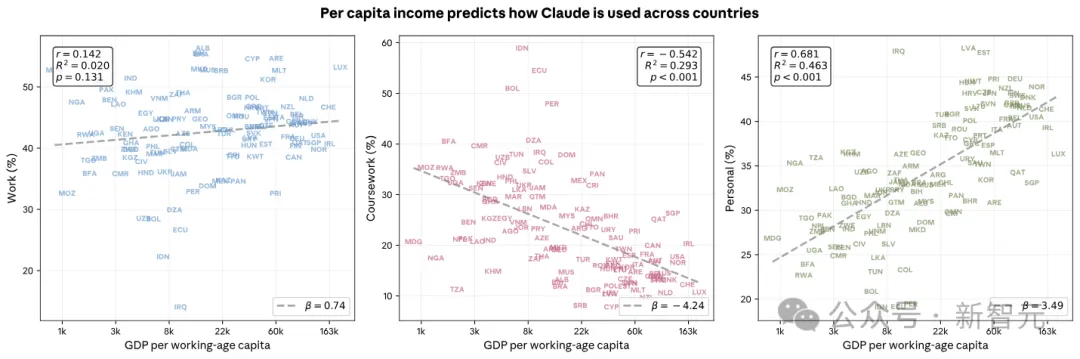

Zooming out to a global scale reveals a clear and somewhat ironic “adoption curve.”

In developed nations with higher per capita GDP, AI is deeply woven into productivity and daily life.

People use it to write code, generate reports, and even plan travel.

In lower-GDP countries, Claude’s primary role is as a “teacher,” with most usage focused on homework and tutoring.

Beyond income disparity, this pattern also reflects a technological gap.

Anthropic notes its partnership with the Rwandan government to help people move beyond basic “learning” into broader applications.

Without intervention, AI risks becoming a new barrier: affluent regions use it to exponentially boost output, while less developed areas are stuck supplementing foundational knowledge.

Workplace Risks: The Shadow of “Deskilling”

The report’s most controversial—and cautionary—section centers on “deskilling.”

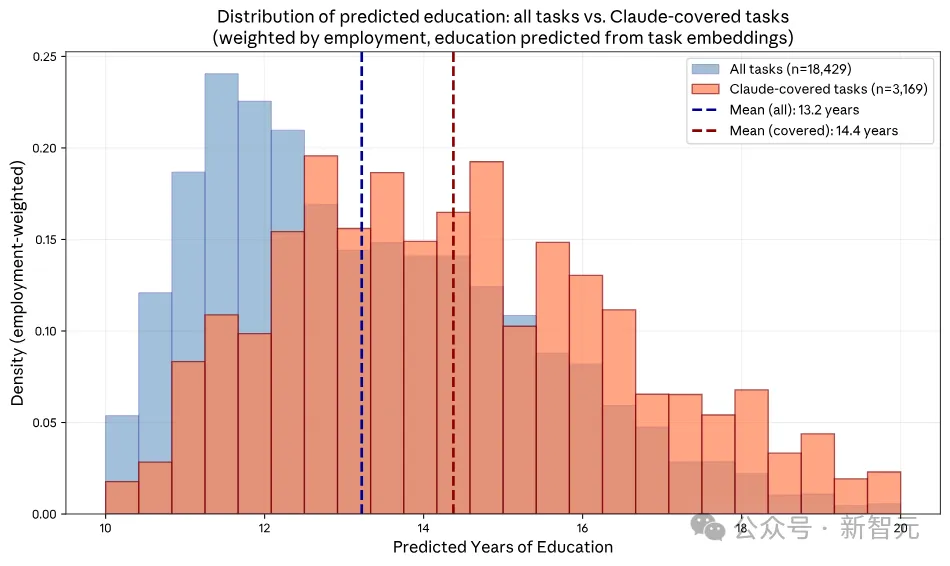

Data shows that the tasks Claude currently covers require an average of 14.4 years of education (comparable to an associate degree), well above the economic average of 13.2 years.

AI is systematically removing the “high-intellect” elements of work.

For technical writers or travel agents, this could be catastrophic.

AI has taken over tasks like industry analysis and complex itinerary planning—jobs that require brainpower—leaving humans with menial chores like sketching or collecting invoices.

Your job survives, but its “value-add” is hollowed out.

There are also beneficiaries.

For example, real estate managers can refocus on high-emotional tasks like client negotiation and stakeholder management after AI handles tedious administrative work—this is “upskilling.”

Anthropic stresses this is a projection based on current trends, not a foregone conclusion.

Still, the warning is real.

If your core strength is handling complex information, you’re at the heart of the storm.

A Return to the “Golden Age” of Productivity?

Let’s close with a macro perspective.

Anthropic has revised its forecast for US labor productivity.

After accounting for potential AI errors and failures, they now expect AI to drive annual productivity growth of 1.0%–1.2% over the next decade.

That’s about a third less than their previous optimistic estimate of 1.8%, but don’t underestimate a single percentage point.

It’s enough to return US productivity growth to the levels of the late-1990s internet boom.

And this is based solely on model capabilities as of November 2025. With Claude Opus 4.5 entering the scene and “enhanced mode” (where users collaborate more intelligently with AI) becoming mainstream, there’s significant upside potential.

Conclusion

Reviewing the report, what stands out isn’t just AI’s growing power, but how rapidly humans are adapting.

We’re experiencing a shift from “passive automation” to “active augmentation.”

In this transformation, AI serves as a mirror, taking over tasks that require high education but can be solved through logic, and pushing us to seek value that algorithms can’t quantify.

In an era of surplus computational power, the rarest human skill is no longer finding answers—it’s defining the questions.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [Synced]. Copyright belongs to the original author [Allen]. For reprint objections, please contact the Gate Learn team, which will process requests promptly according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is explicitly referenced, reproduction, distribution, or plagiarism of translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

Arweave: Capturing Market Opportunity with AO Computer

The Upcoming AO Token: Potentially the Ultimate Solution for On-Chain AI Agents

What is AIXBT by Virtuals? All You Need to Know About AIXBT

AI Agents in DeFi: Redefining Crypto as We Know It

Understanding Sentient AGI: The Community-built Open AGI